One thing I did not really think about the first time I read James Sallis, but that strikes me now on re-reading is the sense of memory being a curse as opposed to a blessing. There’s a moment where Lew Griffin is confronted about his predilection for remembering quotations. “You’re always quoting other people” says the character Verne. “Anytime something important happens or some thought logjams in your head, there you are, hopping up like a schoolboy, pick me! pick me! with what Dante or Camus or Thingamabob said. You think anyone gives half a damn? And half the time, anyway, you’re only using it to avoid digging in, avoid having to find out what you think. Or what you feel.”

I found those lines interesting when I read them in 2003, and I appreciate the irony of my quoting them here, twenty years later. Thing is, I only remember them because I’ve just (re)read them, and because I made a note of them at the time. Written down so I would not forget. Although I did, of course, because I forgot I had written them down.

When I was a student at school I had a jealousy for fellow students who remembered things easily. Most of my classes in the first couple of years of high school were taught in mixed ability groups. Things were always leading towards setting and streaming according to ‘ability’ however, so of course everyone was ranked. Now I always suggest that I am not particularly competitive by nature, but that is doubtless something of a fib because I recall I was always frustrated to some extent not to be top in my group. It was usually between myself, a couple of other boys and three Fiona’s, one of whom was always on top, as it were. Everyone said the secret to this success was that she had photographic memory and I wondered what that would be like. I thought it must be a superpower, but I am no longer sure about that. Great for tests and exams of course, for the education system in the UK, as in most other countries, is built around memory tests more than anything else. But to remember everything? I’d much rather not.

The notion of ‘photographic’ memory is additionally interesting when one considers the photograph, for the photograph is by default selective. What is not within the frame is as important as what is pictured, or at least should be taken into account when thinking about the image. What has been left out? Why? How would the picture be different if the photographer pointed the camera in the other direction? Such considerations can, legitimately, be thought of as ridiculously fussy. My mother would say it is a case of me thinking too much, and she is probably right at that. However, even (especially?) with regards the photographs we make as vessels to hold memory, these questions are valid. What and who does the photograph not show? How does it, over time and repeated viewings, further erase awareness of the surrounding context? How true is it that, when we ask each other (and ourselves) “do you remember when…” we default to remembering the photograph of the when in question. The photograph becomes the memory and vice versa. Again, it is that enchanting dance between the real and imagined, the remembered and the invented.

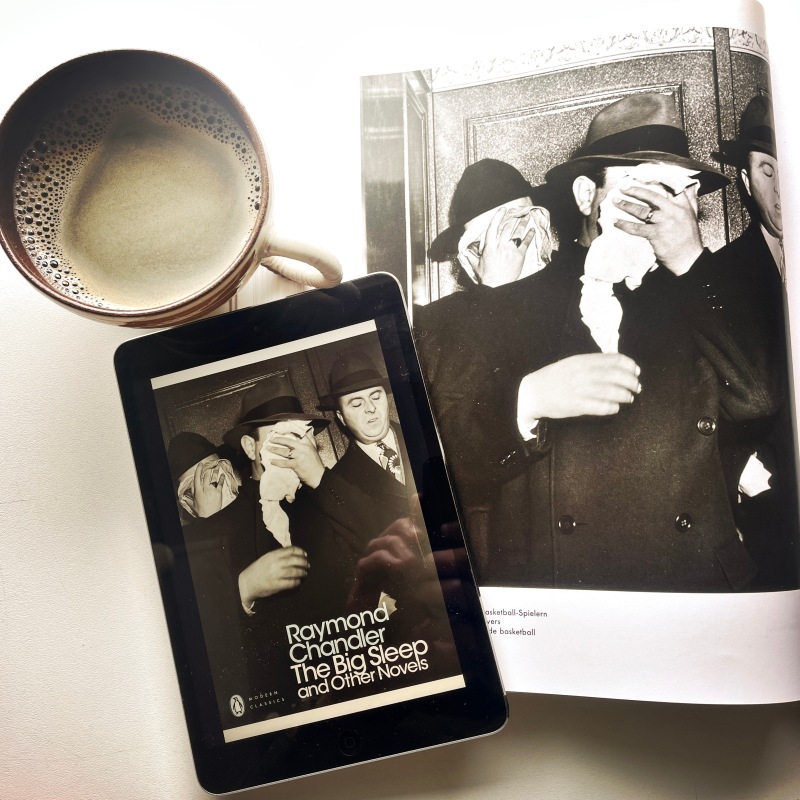

When Penguin books published an omnibus edition of Chandler’s three key novels (‘The Big Sleep’, ‘Farewell My Lovely’ and ‘The Long Goodbye’) at the start of the 21st Century they chose a photograph by American Ukrainian photographer Arthur Fellig for the cover. Better known under the moniker of Weegee, his photographs made in New York throughout the 1930s and 40s have surely constructed much of our cultural memory of time and place. Weegee’s high contrast black and white photographs, particularly the ones of crime and accidents, feel as if they both inform and are informed by the Noir movies of Hollywood. There is a shared visual language going on here between the real and the fictional, and that feeds into the written texts of the pulps. The photograph on that Chandler omnibus cover is of men arrested for bribing basketball players, or so it is captioned in a book of Weegee photographs that I picked up in 1996 and that I have delved into on many occasions since.

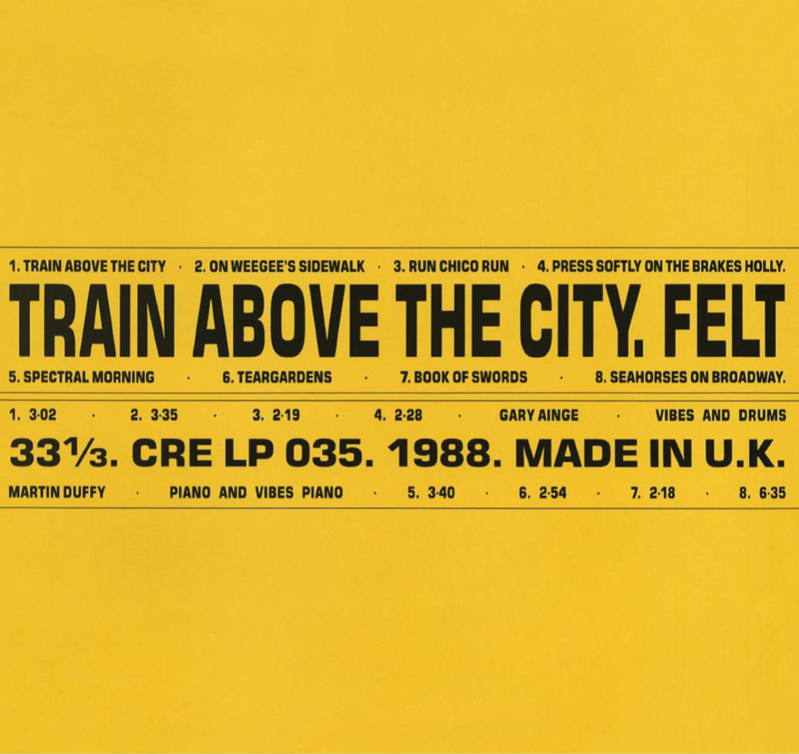

It is probably true that I was not familiar with Weegee’s photographs when I first stumbled on the name as part of a song title by the group Felt. ‘On Weegee’s Sidewalk’ was a track on their penultimate album from 1988, the instrumental ‘Train Above The City’. The record could be a soundtrack to an imaginary Noir movie, the sound of the late Martin Duffy’s vibes evoking a smoky jazz atmosphere of sunlight catching blue smoke as it pierces slatted windows. Sometimes I wish the album had been titled ‘Naked City’ after Weegee’s own first book of photographs published in 1945. It was also the title of a film made three years later by Mark Hellinger, who bought the rights to the name from Weegee. The picture is a gritty investigation into the murder of a model. New York and its streets are the stars.

If ‘Naked City’ had been set in Los Angeles it might have been the story of The Black Dahlia murder. The grotesque 1947 killing of Elizabeth Short has never been officially solved, although there have been any number of intriguing theories. A great book by Mark Nelson and Sarah Hudson Bayliss called ‘Exquisite Corpse’ details the case and draws some compelling lines out to the Art world, particularly that of the surrealists, and Man Ray photographs in particular. It’s a crazy, crazy world, and I suspect that Lawrence of the aforementioned band Felt will have read ‘Exquisite Corpse’ being a bit of a true-crime fan.

A single grim photograph pertaining to the Black Dahlia case opens the terrific outsize book of LAPD archive photographs ‘Scene Of The Crime’ and further into its pages can be found many others that are intriguingly captivating in their forensic matter-of-factness and their connection to the realm of popular culture. In one shot the word ‘PIG’ is smeared on a wall, a grim record of detail from the Cielo Drive murders carried out by Charles Manson’s ‘Family’ in 1969. Elsewhere is a collection of four shots from the scene of Lenny Bruce’s fatal overdose in 1966. The inclusion of a small LAPD ruler to illustrate scale in the two images of bathroom paraphernalia lends the still life arrangements a peculiar grim surrealism, whilst the absence of human presence in the two photographs of Bruce’s book and paper-strewn study is profoundly sad. The blank sheet of paper in the typewriter carries the poignant weight of derelict lost promise.

Author James Ellroy wrote an introduction for ‘Scene Of The Crime’ in 2004 and eleven years later expanded on that to pen a series of short pieces for the more focused ‘LAPD ’53’ book. In its afterward Ellory writes that it was “a stone gas to assemble and write” and his text throughout is full of hep cat beatific Noir flavour. Or flavor, if you prefer. It’s shoot from the hip sharp, and it makes me wonder why I never really investigated more of James Ellroy’s fiction beyond the ‘LA Quartet’ which of course kicks off with his own ‘Black Dahlia’ dance between fact and fiction, Elizabeth Short’s murder being notoriously conflated in the young Ellroy’s brain with the rape and murder of his own mother in 1958. That’s a lot of weight to carry and to process.

One thought on “Carry That Weight”