In the 1963 Poirot novel ‘The Clocks’, as we have seen, Agatha Christie uses one of the rare appearances of her little Belgian detective to engage in an amusing and informative exposition on the history of detective fiction. For the most part this focuses on some key French authors, a smattering of English (it would not do, one assumes, for Christie to be seen to throw either stones or bouquets in her own glass house) and a rogue appearance by the overrated American Mr John Dickson Carter Dickson Carr. When the subject of the hard-boiled ‘tough school’ of detective fiction comes up, however, Poirot dismisses it “much as he would have waved [away] an intruding fly or mosquito.” “‘Violence for violence’ sake?” he continues. “Since when has that been interesting?”

It is a cutting riposte that, in the context of what he has just said about other authors and schools of thought, is perhaps a cute play on Christie’s part to show Poirot as being somewhat old fashioned and out of touch. In 1963, after all, the literary value of the hard-boiled school was surely well established whilst the publicity-seeking fencing between the protagonists on opposite sides of the Atlantic would be largely a thing of the past. Indeed, after a pause for breath and thought, Hercules Christie admits that they rate “American crime fiction on the whole” in “a pretty high place” and considers it “more ingenious, more imaginative than English writing.” One does of course rather wonder just what American crime fiction Agatha Poirot is thinking of here, if not any of the ‘tough school’. Mr John Dickson Carter Dickson Carr? One sincerely hopes not. Ellery Queen then?

When talking about American detective fiction it is likely that the name Ellery Queen was amongst the first I became aware of. Not the novels or short stories, you understand, but the character played by Jim Hutton in the American TV series. Screened in the UK by the BBC in 1976, it is one of the few television shows I can recall watching with the rest of my family. Seeing it again in 2024 is something of a shock of nostalgia, the layers of time travel being overlaid with mis-remembrance. Do I remember the show as being set in the late 1940s? What would that have even meant to a ten year old in 1976? Did I confuse or conflate Jim Rockford’s 1970s California with Jim Hutton’s 1940s New York? When Hutton/Ellery turned to camera, broke the fourth wall and suggested that I was probably way ahead of him and had spotted the murderer, did I ever nod and smugly announce that I was and that I had? As if. What was the fourth wall anyway? And at what point did I realise that there were actual Ellery Queen novels other than the imaginary ones Jim Hutton was writing in the show? History is obscure on the answer to the last one, although I can at least say with some certainty that it was not until 2021 that I finally read some real Ellery Queen books. ‘The French Powder Mystery’, ‘The Spanish Cape Mystery’ and ‘The Greek Coffin Mystery’ all struck me as much more rooted in English detective fiction than the raw rough and tumble of the Black Mask school and whilst they struck me as adequate period pieces they did little to really thrill me. I’m sure that the more puzzle-orientated aspect of Frederic Dannay and Manfred Bennington Lee’s writing as Ellery Queen would have appealed to Poirot and Christie much more than they have done to me, and that is fine of course.

In terms of The Americans though, I am fairly certain that before the Ellery Queen TV show came into my orbit, there would have been a few books on my childhood bookshelf bearing the names of Carolyn Keen and Franklin W. Dixon. Unlike the Famous Five and Agatha Christie paperbacks, none of these Nancy Drew or Hardy Boys titles survived the occasional purges of personal history that I would have scowled through in my teens and twenties, but they are certainly worth thinking about again now, particularly as my rudimentary research about the Ellery Queen TV series suggests that the Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew TV show of 1977-79 was screened by the BBC during 1979. Oddly (or not) I have no recollection of this at all. Archive ‘Radio Times’ listings show that it was broadcast on a late Saturday afternoon, after the Sport and Regional News (‘Scoreboard’ in Scotland ) and before a Rolf Harris show. Has some strange subliminal cancellation process seeped from the Harris reference and erased my Nancy Drew memories? Is memory in fact like ferric cassette or video tape, breaking up over time? Well, mine has clearly unravelled from the case and no amount of rewinding with a pencil is going to help.

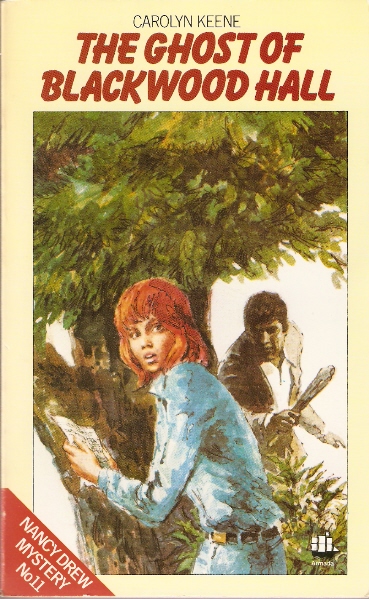

Looking online at the covers of the Drew and Hardy Boys titles published in the UK throughout the 1970s as Armada paperbacks brings slightly more of a flicker of recognition, particularly those yellow box Nancy Drew covers with the Peter Arthur illustrations. These may not be particularly memorable from a design perspective, but I admit that the sight of a red headed Nancy glancing over her shoulder in an anxious manner stirs the ancient memory of a ten year old’s crush. This is another piece of evidence for my not having seen the TV series, for I feel sure that my thirteen year old self could not have failed to have found Pamela Sue Martin incredibly crush-worthy. Then again, at that age I would have struggled to see further than a girl called Veronica who sat beside me in Chemistry classes. This, of course, decades before she would find fame on British television screens as Ronni Ancona and surprise me by cropping up as Steve Coogan’s PA in the tremendous second series of ‘The Trip’. Seeing her there on screen oddly transported me back to 1979, sitting at the bottom of the stairs for hours trying to summon the courage to phone her number and ask her out. The anti-climax of finally hearing her say ‘no’ was, of course, savagely dispiriting. The following week she had moved tables in Chemistry and to say I missed hearing her passionate raving about Dustin Hoffman in my ear would be an understatement. I wonder if she ever read Nancy Drew stories? Wonder too if she was ever famous enough to get to meet Hoffman in person. I hope so.

I did re-read some Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew stories recently and found it an interesting experience. The first few Drew novels, ghostwritten in the early 1930s by Mildred Wirt Benson still read as thoroughly enjoyable mystery adventures. Wholesome fun, fired through with the kind of old-fashioned conservative American family values that knee-jerk jerks of a right leaning proclivity might suggest they are fighting to protect today. Nonsense, of course, for what comes over in these early Drew stories is a fundamental sense of decency and fairness that would seem to be anathema to much of 21st Century America. Shame.

Have The Hardy Boys aged as handsomely? Well, not to my eyes, although this is admittedly based on a very small selection of Leslie McFarlane penned books from the late 1920s and early 1930s. These, such as the 1928 title ‘Hunting For Hidden Gold’, read now as ridiculously robust action adventures that are fuelled more by testosterone and machismo than by anything so subtle as a mystery to be solved. Did I enjoy this kind of nonsense as a ten year old? I like to think not so much, and see this is a reason for their exclusion from those bookshelves where Enid Blyton was allowed to stay. Nancy Drew should certainly have been given a reprieve though.

Then there would be the Three Investigators books. Or, more accurately, ‘Alfred Hitchcock and The Three Investigators’. In truth these would have been my brother’s paperbacks and I know there are at least a couple still surviving in our childhood home. Indeed, we were discussing them just recently, me in the midst of some re-reading and him going through the tortuous process of remembering The Past. It is interesting how some very clear specific memories can become ensnared by other flickers of recollection, a process which itself transforms that specific reality into something different. For example, my brother vividly recalls something about how ultra-low frequency sounds, whilst being inaudible to our ears, can nevertheless generate feelings of unease and terror. He remembers reading that when he was a young boy and credits this with being the start of a lifetime’s interest in science. The thing is, he has for many years put that memory together with Enid Bylton’s Secret Seven books (he was Secret Seven, I was Famous Five), whilst in fact it is something that is key to the solution of the first Three Investigators book, ‘The Secret of Terror Castle’. Now whilst I know I also read ‘Terror Castle’ as a youngster that fact about low-frequencies made little or no impact, and it was only my recent re-reading that allowed me to reposition the ‘truth’ in my brother’s memory. Part of me feels guilty about this, a sadness at fracturing a decades old connection for him between Blyton and the mysteries of science. Part of me too wonders what ‘truth’ will stick in, say, another ten or twenty years time. Will the neural connections long established in my brother’s brain between The Secret Seven and low frequency oscillation reestablish themselves and once again triumph over the ‘reality’? There’s a science experiment for him to ponder.

So there is certainly something interesting about the pursuit of cold scientific proof in The Three Investigators. It’s all very ‘Scooby Doo’, particularly in the first few books, in that the mysteries of haunted houses, spectral apparitions and whispering Egyptian mummies can be debunked by the application of cool deduction and scientific process. And yes, the adult criminals would have gotten away with it if it hadn’t been for the pesky kids…

There is also something interesting about the Three Investigators books being in many ways promotional materials for The American Dream. Start a business! Get a celebrity endorsement! Design a memorable logo and branding! Promote yourselves at every opportunity! Run another job on the side! Work all the hours under the sun! It’s all there. Of course the capitalist propagandising of those themes was way over my head as a ten year old but they stand out strongly when reading them again in 2024. Yet what also comes over in at least the early books is something about the triumph of the nerdy outsider. The Three Investigators may not be wacky Out There weirdoes, but neither are they the kind of archetypal privileged Californian kid that we were encouraged to despise in, say, John Hughes’ films of the 1980s. That kind of young adult is embodied by the Skinny Norris character in The Three Investigators, and although his is at best a bit part, he does remind us what Jupiter Jones, Pete Crenshaw and Bob Andrews are not. What they are is irregular regular kids, characters who inhabit a strange kind of mediated middle ground in society, strangely untouched by the weird Pop Sub-Cultural happenings that would have been exploding around them in their contemporary mid to late 1960s California. These early books penned by Robert Arthur at least seem to exist in a strange pre-Pop realm, one that casts back to a pre-war Hollywood, which is apt given that by 1964 Alfred Hitchcock had the vast majority of his film-making career behind him. The preponderance of Egyptian mummies, movie stars of the silent screen and the abandoned mansions and estates of dubious 19th Century merchants makes The Three Investigators seem like conduits for conservative nostalgia. Again, this would have been lost on a ten year old in 1976 as it likely would have been on a ten year old in 1966. Yet this layering of nostalgia, where multiple coats of mediated memory have built up over the space of many decades now lend these books a peculiar patina. They belong elsewhere, or at least elsewhen, and part of their charm now is that they no longer seem to know what that might be themselves.

I know how that feels.

One thought on “Investigating nostalgia with young Americans”